This page is currently in the process of being re-designed, updated and revised.

Richard Burton People

Compiled below is a list of people who, in their own way played a part in, or had a major influence on, the life and career of Richard Burton. Although mentioned in passing on various other pages of this site, they deserve a more detailed profile of their own.

The Richard Burton Museum does not own the rights or copyright to any of the images reproduced below, but have tried hard to credit the respective owners where possible.

The Richard Burton Museum does not own the rights or copyright to any of the images reproduced below, but have tried hard to credit the respective owners where possible.

Edith Maud Jenkins, nee Thomas

Richard Burton's mother was born Edith Maud Thomas, in Llangffelach, South Wales, a small village located just ten miles from Pontrhydyfen, on the 28th of January 1883.

Edith Maud was the eldest daughter of a respectable, middle-class Methodist Welsh family. Her father Harry, originally a miner, was later to rise up the ladder to become a significant member of the management in a local copper smelting works.

Edith Thomas first met Richard Burton's father when she was employed as a barmaid in The Miners Arms, Pontrhydyfen, and after a courtship lasting well over a year, finally agreed to marry Dic Jenkins, against the wishes of her family, on the Christmas Eve of 1900 at Neath Registry Office. Edith was forced to lie about her age on the Marriage Certificate as she was under eighteen at the time and needed her parents permission to marry, obviously something which she knew would never be granted to her.

Edith's story is such a tragic one. Having found out about the illicit marriage, Edith's parents disowned her and for the next twenty-five years she was subjected to the worst kind of treatment possible from her alcoholic, abusive husband. Edith was often left penniless and unable to feed her growing family due to her husband's continual drinking binges, Dic Jenkins often disappearing with the housekeeping money for the public houses of Swansea and Neath for days, sometimes weeks, on end.

David Jenkins, Richard's elder brother, was the only member of the family to write of the few memories he had of his mother. In his biography of Richard, entitled, 'A Brother Remembered' he wrote of Edith saying..."It is tempting to idealise my mother as the pure selfless one, devoted to children and home, and to condemn my father for his self-absorption and gratification, and his humiliation of his family. She rarely, if ever, questioned her total subjugation to the family and devotion to chapel; the idea of her doing something for her own pleasure was quite alien to her".

From the age of eighteen until her death, Edith was to give birth to thirteen children, which included the birth of two daughters, both called Margaret Hannah, who died in infancy. By the time Edith was to give birth to her thirteenth child, Richard Burton's younger brother Graham on the 25th of October 1927, she was physically and emotionally exhausted, mainly due to neglect and poverty. Her final indignity came when Dic Jenkins refused her any money for hospital care when she was diagnosed with septicemia soon after the birth.

Edith Jenkins succumbed to the illness just six days later, dying at home on the morning of the 31st of October, 1927. She was just forty-five years of age.

David Jenkins was further to recall in his marvellous book, 'A Brother Remembered'..."On the morning of the 31st of October, there was suddenly a frightening atmosphere in the house. I can remember the confused, fearful feelings I had, unable to understand exactly what was going on, certain only of the magnitude of the ill-defined disaster. (Prior to this David Jenkins had sensed that all was not well, his mother had borne for many years, virtually single-handedly, the burden of family responsibility, often going without food herself to be able to feed her children, making her emotionally and physically weak.) The doctor and midwife, my father and Cis were rushing about the house in a state of confused preoccupation. I was the only child in the house that morning. About nine o'clock my father came faltering down the stairs and I realised with mounting horror that he was saying to me, 'Mae dy fam wedi marw..'Your mother has died'.

In a moment of melancholy during an interview in his later years Richard Burton was to recall that;

"Apparently I was a real mother's boy, I went with her everywhere, I hung on to her, but I think the shock must have been so great that when they told me she had gone away and that she wouldn't come back, which I don't remember being told, I never asked for her again. I completely, obviously, cut her out of my two year old mind and I have no recollection of her whatsoever. It must be sleeping there in some dormant part of the brain, but I'm not sure I would like to remember..."

Richard Burton's mother was born Edith Maud Thomas, in Llangffelach, South Wales, a small village located just ten miles from Pontrhydyfen, on the 28th of January 1883.

Edith Maud was the eldest daughter of a respectable, middle-class Methodist Welsh family. Her father Harry, originally a miner, was later to rise up the ladder to become a significant member of the management in a local copper smelting works.

Edith Thomas first met Richard Burton's father when she was employed as a barmaid in The Miners Arms, Pontrhydyfen, and after a courtship lasting well over a year, finally agreed to marry Dic Jenkins, against the wishes of her family, on the Christmas Eve of 1900 at Neath Registry Office. Edith was forced to lie about her age on the Marriage Certificate as she was under eighteen at the time and needed her parents permission to marry, obviously something which she knew would never be granted to her.

Edith's story is such a tragic one. Having found out about the illicit marriage, Edith's parents disowned her and for the next twenty-five years she was subjected to the worst kind of treatment possible from her alcoholic, abusive husband. Edith was often left penniless and unable to feed her growing family due to her husband's continual drinking binges, Dic Jenkins often disappearing with the housekeeping money for the public houses of Swansea and Neath for days, sometimes weeks, on end.

David Jenkins, Richard's elder brother, was the only member of the family to write of the few memories he had of his mother. In his biography of Richard, entitled, 'A Brother Remembered' he wrote of Edith saying..."It is tempting to idealise my mother as the pure selfless one, devoted to children and home, and to condemn my father for his self-absorption and gratification, and his humiliation of his family. She rarely, if ever, questioned her total subjugation to the family and devotion to chapel; the idea of her doing something for her own pleasure was quite alien to her".

From the age of eighteen until her death, Edith was to give birth to thirteen children, which included the birth of two daughters, both called Margaret Hannah, who died in infancy. By the time Edith was to give birth to her thirteenth child, Richard Burton's younger brother Graham on the 25th of October 1927, she was physically and emotionally exhausted, mainly due to neglect and poverty. Her final indignity came when Dic Jenkins refused her any money for hospital care when she was diagnosed with septicemia soon after the birth.

Edith Jenkins succumbed to the illness just six days later, dying at home on the morning of the 31st of October, 1927. She was just forty-five years of age.

David Jenkins was further to recall in his marvellous book, 'A Brother Remembered'..."On the morning of the 31st of October, there was suddenly a frightening atmosphere in the house. I can remember the confused, fearful feelings I had, unable to understand exactly what was going on, certain only of the magnitude of the ill-defined disaster. (Prior to this David Jenkins had sensed that all was not well, his mother had borne for many years, virtually single-handedly, the burden of family responsibility, often going without food herself to be able to feed her children, making her emotionally and physically weak.) The doctor and midwife, my father and Cis were rushing about the house in a state of confused preoccupation. I was the only child in the house that morning. About nine o'clock my father came faltering down the stairs and I realised with mounting horror that he was saying to me, 'Mae dy fam wedi marw..'Your mother has died'.

In a moment of melancholy during an interview in his later years Richard Burton was to recall that;

"Apparently I was a real mother's boy, I went with her everywhere, I hung on to her, but I think the shock must have been so great that when they told me she had gone away and that she wouldn't come back, which I don't remember being told, I never asked for her again. I completely, obviously, cut her out of my two year old mind and I have no recollection of her whatsoever. It must be sleeping there in some dormant part of the brain, but I'm not sure I would like to remember..."

Richard Walter Jenkins Senior

Richard Walter Jenkins Senior was born on the 5th of March,1876 in Efail-Fach, South Wales, to parents Thomas and Margaret Jenkins, a working-class mining family originally from Pontrhydyfen. Dic Bach, as he became known, meaning 'Little Dick' due to his small stature, was named after his maternal grandfather, Richard Walter, who had at one time been the manager of the Pontrhydyfen mill.

Taking after his father Thomas, Dic, from an early age was an irresponsible, selfish, drunken gambler, whose sole pleasure seemed to be drinking away the seven shillings and six pence which he earned from his employment working down the coal-mines of Pontrhydyfen, a job he had held since the age of fourteen.

Dic Jenkins, although having the reputation as a drinker and a man not be trusted, was however, according to his elder sons, an intelligent, well-read and literate man, who spoke both Welsh and English fluently. He was also a talented pit-worker and was renowned throughout the South Wales valley's for his skills. He rapidly rose to earning three pounds a week and became somewhat of a hero in the mining community. Dic Jenkin's weaknesses however were alcohol and gambling, two vices which left him frequently broke, and a borrower of money which he would never pay back, and increasingly unreliable as an employee.

Despite these failings, Dic Jenkins was a born raconteur and storyteller, (a trait obviously passed on to his famous son), and he had a charm and wit that overshadowed the fact that he was a waster and a drunkard. This charm must have worked on Edith Maud Thomas in the early days of their courtship for she was to say that it was his 'eloquence and deep rooted passion' which had made her overlook his more serious faults. A decision she must have regretted throughout the ensuing and turbulent years of her marriage.

After Edith died and the younger children had been taken to the homes of their elder siblings to be raised, Dic Jenkins, now a sad, lonely and haunted figure, looking considerably older than his years, went into a slow alcoholic decline that would take thirty years to complete. Spending most of his days and nights in The Miners Arms and at other times, according to David Jenkins .." Just pottering around the house when he was there, not greatly missed when he was not.", it seemed that he had accepted the fact that his older children were now in charge of the day-to-day running of the house, and also, his life. It was Hilda, Richard Burton's sister, who would remain closest to her father, and as the elder children moved on with their lives, getting married and leaving home, it was Hilda who took responsibility for the welfare of Dic Jenkins. Eventually too, Hilda would get married and leave 2 Dan-Y-Bont forever, and when she did, she took her aged, alcoholic father with her.

Dic Jenkins was always to be a neglectful and absent father, neither taking an interest or pride in any of his children's scholastic or life achievements. Sadly this was especially true in Richard's case. It has been well documented that Dic Jenkins only ever saw one of Richard Burton's films, probably 'My Cousin Rachel', taken on a family night-out to the Cardiff Premiere but leaving half-way through the screening to find a local pub, complaining that..."There was too much kissing".

The end for Dic Jenkins finally came on the 25th of March, 1957 at the Neath General Hospital, having been taken there the week previously due to breathing problems. Richard Burton received the news, by telegram, at his home in Celigny. David Jenkins was to remark that..."And so it was that I was to be the one person present at the death of both my parents. My father's death was nowhere near as traumatic as my mother's had been for her young children, but it was nonetheless a great wrench"

In what was to be a final, very telling gesture, Richard Burton did not attend the funeral.

Richard Walter Jenkins Senior was born on the 5th of March,1876 in Efail-Fach, South Wales, to parents Thomas and Margaret Jenkins, a working-class mining family originally from Pontrhydyfen. Dic Bach, as he became known, meaning 'Little Dick' due to his small stature, was named after his maternal grandfather, Richard Walter, who had at one time been the manager of the Pontrhydyfen mill.

Taking after his father Thomas, Dic, from an early age was an irresponsible, selfish, drunken gambler, whose sole pleasure seemed to be drinking away the seven shillings and six pence which he earned from his employment working down the coal-mines of Pontrhydyfen, a job he had held since the age of fourteen.

Dic Jenkins, although having the reputation as a drinker and a man not be trusted, was however, according to his elder sons, an intelligent, well-read and literate man, who spoke both Welsh and English fluently. He was also a talented pit-worker and was renowned throughout the South Wales valley's for his skills. He rapidly rose to earning three pounds a week and became somewhat of a hero in the mining community. Dic Jenkin's weaknesses however were alcohol and gambling, two vices which left him frequently broke, and a borrower of money which he would never pay back, and increasingly unreliable as an employee.

Despite these failings, Dic Jenkins was a born raconteur and storyteller, (a trait obviously passed on to his famous son), and he had a charm and wit that overshadowed the fact that he was a waster and a drunkard. This charm must have worked on Edith Maud Thomas in the early days of their courtship for she was to say that it was his 'eloquence and deep rooted passion' which had made her overlook his more serious faults. A decision she must have regretted throughout the ensuing and turbulent years of her marriage.

After Edith died and the younger children had been taken to the homes of their elder siblings to be raised, Dic Jenkins, now a sad, lonely and haunted figure, looking considerably older than his years, went into a slow alcoholic decline that would take thirty years to complete. Spending most of his days and nights in The Miners Arms and at other times, according to David Jenkins .." Just pottering around the house when he was there, not greatly missed when he was not.", it seemed that he had accepted the fact that his older children were now in charge of the day-to-day running of the house, and also, his life. It was Hilda, Richard Burton's sister, who would remain closest to her father, and as the elder children moved on with their lives, getting married and leaving home, it was Hilda who took responsibility for the welfare of Dic Jenkins. Eventually too, Hilda would get married and leave 2 Dan-Y-Bont forever, and when she did, she took her aged, alcoholic father with her.

Dic Jenkins was always to be a neglectful and absent father, neither taking an interest or pride in any of his children's scholastic or life achievements. Sadly this was especially true in Richard's case. It has been well documented that Dic Jenkins only ever saw one of Richard Burton's films, probably 'My Cousin Rachel', taken on a family night-out to the Cardiff Premiere but leaving half-way through the screening to find a local pub, complaining that..."There was too much kissing".

The end for Dic Jenkins finally came on the 25th of March, 1957 at the Neath General Hospital, having been taken there the week previously due to breathing problems. Richard Burton received the news, by telegram, at his home in Celigny. David Jenkins was to remark that..."And so it was that I was to be the one person present at the death of both my parents. My father's death was nowhere near as traumatic as my mother's had been for her young children, but it was nonetheless a great wrench"

In what was to be a final, very telling gesture, Richard Burton did not attend the funeral.

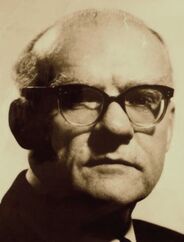

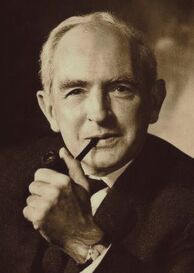

Philip H. Burton

Philip Henry Burton was born on the 30th of November, 1904 in Mountain Ash, South Wales, to an English father and a Welsh mother. His father died in a pit accident when Philip was just fourteen, and this led Philip Burton to withdraw into himself and focus his attention on his schoolwork, literature and the arts. Philip Burton excelled at school and largely due to his mothers influence, who saw the academic promise in her son, Philip applied for, and won a scholarship for a place at the University of Wales based in Cardiff, and graduated in 1925 with a double honours degree in mathematics and history.

It was while he was studying in Cardiff that Philip Burton really discovered the theatre. The capital of Wales, Cardiff, in the years between the wars, was a cultural goldmine, boasting three of the grandest theatres of the time, The Empire, The New Theatre and The Playhouse. Philip Burton spent as much time as his studies would allow watching productions and learning the techniques as to how each performance was staged, and the creative process that went into each and every show. It was during this time that he knew his vocation in life was to be involved in some way with the theatre, whether it be as an actor or involved in the production process, perhaps as a script editor, or possibly as a director.

After graduating from university, Philip Burton took up a post at the Port Talbot Secondary School, where he became the senior English master. He also became the chairman of the Port Talbot Y.M.C.A. and founded the accompanying Drama Society.

It was during this time that Philip Burton was also contributing plays to the B.B.C. in Cardiff, and two of his plays, 'Granton Street' and 'Margam Abbey' were broadcast in 1937, produced by T. Rowland Hughes, who he continued to work with throughout the War years.

Philip Burton was a prolific writer and between 1937 and 1953 provided the B.B.C. with well over forty-five completed radio scripts, as well as screenplays for television dramas. This incredible body of work led Philip Burton to be awarded a scholarship by the University of Wales to visit America to study drama, broadcasting and theatre, this he duly undertook in 1938.

Returning to Britain just before the War, Philip Burton was commissioned as Commanding Officer of the Port Talbot Air Training Corps, 499 Squadron, a post which led to him being awarded an M.B.E.

Since his youth, Philip Burton had always longed to be an actor, and as Head English master at the Port Talbot Secondary school he had every opportunity to discover a young protege who could achieve success on the stage which had long eluded himself. This he did very successfully with a young pupil named Owen Jones, who would go on to appear in many films in the 1930's as well as appearing with many great names on the theatrical stage. Sadly, Owen Jones was called-up during the War to serve in the Royal Air Force, and died after an accident during training, which left Philip Burton devastated. It was following this that the outstanding talent of another young pupil, Richard Walter Jenkins, came to the attention of Philip Burton, who immediately took the aspiring young talent under his wing.

Philip Burton tutored Richard Jenkins mercilessly, often working together into the early hours, teaching him his usual school subjects as well as the rudiments of stage work, elocution and acting voice, which included hours of outdoor voice projection on the mountains overlooking Port Talbot. Richard Burton was to later recall these lessons as the most hardworking and painful period of his life.

During the early 1940's, Philip Burton made an unsuccessful attempt to adopt the young Richard Jenkins in order to give him a better chance of succeeding in his chosen profession, but due to a technicality was only able to make him his legal ward, but this gave Richard Jenkins Burton's surname and propelled him on the way to international stardom. There is no doubt that without Philip Burton and his knowledge, dedication, foresight and educational discipline there would have been no Richard Burton, the actor.

Philip Burton left teaching in 1945 and took over from T. Rowland Hughes as the Features Producer for B.B.C. Wales. One of his first jobs within the B.B.C. was to produce the Dylan Thomas radio feature, 'Return Journey'. He was to work closely with Dylan Thomas during the first draft of the radio play, 'The Town That Was Mad', which would later to become Dylan's 'Play for Voices', 'Under Milk Wood'.

In 1949 Philip Burton left the B.B.C. in Cardiff and moved to London to take up the position of Chief Instructor at the B.B.C. Staff Training School. A year later he was promoted to the Welsh Committee of the Arts Council.

He left the B.B.C. in 1952 to become a freelance scriptwriter, and began by writing the first twelve episodes of the first ever B.B.C. television 'Soap Opera', entitled 'The Appleyards'.

In 1954, Philip Burton moved to America where he helped establish the American Musical and Dramatic Academy and became its first Director. He eventually became an American citizen in 1964 and retired to Key West in Florida where he died in Haines City, aged ninety, on the 28th of January, 1995.

Philip Henry Burton was born on the 30th of November, 1904 in Mountain Ash, South Wales, to an English father and a Welsh mother. His father died in a pit accident when Philip was just fourteen, and this led Philip Burton to withdraw into himself and focus his attention on his schoolwork, literature and the arts. Philip Burton excelled at school and largely due to his mothers influence, who saw the academic promise in her son, Philip applied for, and won a scholarship for a place at the University of Wales based in Cardiff, and graduated in 1925 with a double honours degree in mathematics and history.

It was while he was studying in Cardiff that Philip Burton really discovered the theatre. The capital of Wales, Cardiff, in the years between the wars, was a cultural goldmine, boasting three of the grandest theatres of the time, The Empire, The New Theatre and The Playhouse. Philip Burton spent as much time as his studies would allow watching productions and learning the techniques as to how each performance was staged, and the creative process that went into each and every show. It was during this time that he knew his vocation in life was to be involved in some way with the theatre, whether it be as an actor or involved in the production process, perhaps as a script editor, or possibly as a director.

After graduating from university, Philip Burton took up a post at the Port Talbot Secondary School, where he became the senior English master. He also became the chairman of the Port Talbot Y.M.C.A. and founded the accompanying Drama Society.

It was during this time that Philip Burton was also contributing plays to the B.B.C. in Cardiff, and two of his plays, 'Granton Street' and 'Margam Abbey' were broadcast in 1937, produced by T. Rowland Hughes, who he continued to work with throughout the War years.

Philip Burton was a prolific writer and between 1937 and 1953 provided the B.B.C. with well over forty-five completed radio scripts, as well as screenplays for television dramas. This incredible body of work led Philip Burton to be awarded a scholarship by the University of Wales to visit America to study drama, broadcasting and theatre, this he duly undertook in 1938.

Returning to Britain just before the War, Philip Burton was commissioned as Commanding Officer of the Port Talbot Air Training Corps, 499 Squadron, a post which led to him being awarded an M.B.E.

Since his youth, Philip Burton had always longed to be an actor, and as Head English master at the Port Talbot Secondary school he had every opportunity to discover a young protege who could achieve success on the stage which had long eluded himself. This he did very successfully with a young pupil named Owen Jones, who would go on to appear in many films in the 1930's as well as appearing with many great names on the theatrical stage. Sadly, Owen Jones was called-up during the War to serve in the Royal Air Force, and died after an accident during training, which left Philip Burton devastated. It was following this that the outstanding talent of another young pupil, Richard Walter Jenkins, came to the attention of Philip Burton, who immediately took the aspiring young talent under his wing.

Philip Burton tutored Richard Jenkins mercilessly, often working together into the early hours, teaching him his usual school subjects as well as the rudiments of stage work, elocution and acting voice, which included hours of outdoor voice projection on the mountains overlooking Port Talbot. Richard Burton was to later recall these lessons as the most hardworking and painful period of his life.

During the early 1940's, Philip Burton made an unsuccessful attempt to adopt the young Richard Jenkins in order to give him a better chance of succeeding in his chosen profession, but due to a technicality was only able to make him his legal ward, but this gave Richard Jenkins Burton's surname and propelled him on the way to international stardom. There is no doubt that without Philip Burton and his knowledge, dedication, foresight and educational discipline there would have been no Richard Burton, the actor.

Philip Burton left teaching in 1945 and took over from T. Rowland Hughes as the Features Producer for B.B.C. Wales. One of his first jobs within the B.B.C. was to produce the Dylan Thomas radio feature, 'Return Journey'. He was to work closely with Dylan Thomas during the first draft of the radio play, 'The Town That Was Mad', which would later to become Dylan's 'Play for Voices', 'Under Milk Wood'.

In 1949 Philip Burton left the B.B.C. in Cardiff and moved to London to take up the position of Chief Instructor at the B.B.C. Staff Training School. A year later he was promoted to the Welsh Committee of the Arts Council.

He left the B.B.C. in 1952 to become a freelance scriptwriter, and began by writing the first twelve episodes of the first ever B.B.C. television 'Soap Opera', entitled 'The Appleyards'.

In 1954, Philip Burton moved to America where he helped establish the American Musical and Dramatic Academy and became its first Director. He eventually became an American citizen in 1964 and retired to Key West in Florida where he died in Haines City, aged ninety, on the 28th of January, 1995.

A studio portrait of a young Richard Jenkins seated with his foster father, Philip Burton. The photograph is credited to the Philip Burton Collection.

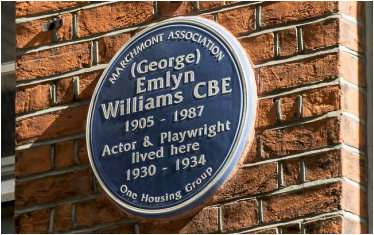

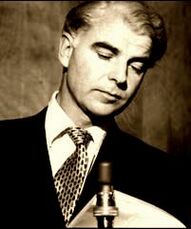

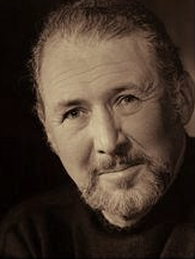

George 'Emlyn' Williams

George Emlyn Williams was born in Glan-Yr-Afon, Mostyn, Flintshire on the 26th of November, 1905.

After being schooled at Hollywell Grammar School, for which he had won a scholarship, he attended Christ Church, Oxford, where he read French and Italian and joined the Oxford University Dramatic Society, which was where he discovered his taste for the theatre and in particular his talent in the art of play-writing.

In 1927, at the age of eighteen, Emlyn Williams joined a small repertory company and by 1930 had begun writing himself, his early works included the titles, 'A Murder Has Been Arranged' and 'The Late Christopher Bean', a successful comedy-drama which opened at The St. James Theatre, London on May the 16th,1933 and which ran for a total of four hundred and thirty-three performances.

It was however his 1935 play, 'A Night Must Fall', that brought him recognition and fame. 'Night Must Fall', was a psychological thriller which was later adapted twice for film, the first, and most successful being in 1937 which starred Robert Montgomery and Rosalind Russell.

Success followed success and in 1938 he wrote 'The Corn Is Green', probably the play which Emlyn Williams will be most remembered for. This too was adapted for the big screen, being released in 1945 by Warner Brothers and starring two great character actors, Bette Davis and Nigel Bruce.

It was in 1944 however, with his next play, 'The Druid's Rest', that Emlyn Williams became involved in the life, and career, of Richard Burton.

More information on 'The Druid's Rest' and Emlyn Williams' involvement in the life and career of Richard Burton can be found on the 'Richard Burton In The Theatre' and 'Burton Books and Magazines' pages of this website.

As well as stage-plays, Emlyn William's was a prolific writer of screenplays, which included working with Alfred Hitchcock on 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' which was released in 1956 by Paramount Pictures and starred James Stewart and Doris Day.

Emlyn Williams also began to appear in various films himself including the classic films, 'They Drive By Night', 'The Citadel', 'Jamaica Inn', and of course, 'The Last Day's Of Dolwyn'.

Written and directed by, and starring Emlyn Williams himself, 'The Last Day's Of Dolwyn' is notable for being the film in which Richard Burton would make his screen debut. In a part especially written for him, Richard Burton would play the role of Gareth, a part requiring him to speak both Welsh and English, starring alongside Edith Evans, Hugh Griffith and Emlyn Williams himself.

As well as appearing in his own plays, Emlyn Williams took two 'one-man shows' on tour, the first in which he portrayed Charles Dickens and the second, Dylan Thomas in the production entitled, 'A Boy Growing Up'.

Emlyn Williams was also the author of two autobiographies and the best selling 'True-Crime' work, 'Beyond Belief - A Chronicle of Murder and Detection', which was an in-depth study of the infamous 'Moors Murders' of the late sixties.

From 1935 Emlyn Williams was married to the actress Mary O' Shann with whom they had two sons, Alan, who became a writer, and Brook, who became close to Richard Burton and was employed by him as a personal assistant and who can often be seen in many of Richard Burton's films in small cameo roles.

Emlyn Williams was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1962.

A lifelong friend of Richard Burton, he was instrumental in the introduction of Burton to his first wife Sybil, was Godfather to Burton's daughter Kate, and read a moving eulogy at Richard Burton's Memorial Service, held in London, in August, 1984. A deeply personal and moving piece of writing, it reads in it's entirety;

Our dear Richard...Or, the way I used to start a letter to you - Annwyl Richard...Our dear Richard, here we all are, joining Sally and Kate and all your family in thinking about you, and talking about you. Yes, I can see the old twinkle in the eye, as if to say - 'Well, now that the smoke's clearing away...what are you going to say about me? Not going to be easy, is it?' How often, in the past few weeks, have my thoughts gone back to the first time you and I met, forty-one years ago next month! We spoke of that first meeting, you remember, at our last meeting, in New York a year ago...

It was one evening in Cardiff, in 1943, the Sandringham Hotel, where I was interviewing possible Welsh-speaking actors for a new play. After a dismal procession of no-goods, an older man introduced himself as the schoolmaster who had written about a pupil, apparently a promising amateur. He beckoned, and the pupil stepped forward : a boy of seventeen, of startling beauty, and quiet intelligence. He looked - as very special human beings tend to look at that age - he looked imperishable.

I asked young Jenkins what was the last part he had played, at school. The answer came clear as a bell, 'Professor Higgins in Pygmalion.' I was later to realise the added incongruity of that : the schoolmaster - the unique Phil Burton - was, at that time, playing a real-life Higgins to a markedly male Eliza.

At rehearsals in London, it was interesting to watch the boy work, for he did something very rare : he drew attention by not claiming it. He played his part with the perfect simplicity needed, and offstage was quietly pleasant - not shy, just...reserved - except for the sudden smile, which - there is no other word for it - glowed. He didn't talk much. I think he was a bit self-conscious about his accent, and the need to work on it - it's a phase actors sometimes go through. But inside there, there was humour. A twinkle in the eye, no doubt about it. One evening, as he and I walked away from a late rehearsal, I asked what was the book he was carrying. 'Dylan Thomas'. I just knew the name. 'He is a great poet.' Then he suddenly stopped, and recited. The words resounded through the blackout of the deserted street : Upper St.Martin's Lane, just up the road. 'They shall have stars at elbow and foot...'

I did not say to myself, in a flash, 'This lad will be famous!' But it did occur to me that here was more than a well-graced adolescent who could speak lines naturally, this was a 'voice'. And behind the 'voice' a mind which, like my own, was in love with the English language.

Then I asked him, in an avuncular manner - I was thirty-seven - if his digs were all right, and was he behaving himself in London? he said he was. Even then I doubted it.

Oh, the English language - let me touch, in passing, on something which - up till now - has only been known by those closest to him. His devotion to spoken English has over the last years, extended to words on paper. Steadily, unobtrusively, he has been writing. Diaries? Autobiography? Time will tell, and may surprise. Anyway...

Back to spoken English. After the war, five years of invaluable stage experience, with in between, several films. Then in the early fifties, the young actor's life was taken over by Shakespeare, at 'Stratford' and the 'Old Vic'. They were salaries you couldn't save on, but gruelling hard work built up to triumph.

My former school-teacher, Miss Cooke, was curious about this second Welsh peasant who had been seduced into the theatre and I presented him to her. Richard was on his best behaviour. But she did say afterwards, 'He's going to do well, what's more he's got the devil in him. You haven't.' I felt commonplace.

Then - America! The Movies, Capital 'M', and - and even bigger capital 'M' - the money! The dollars poured in.

Then - 1962. Which means we have to touch lightly - no names mentioned - on a certain Roman - Egyptian epic. (I nearly said 'a Roman - Elizabethan epic')...Gossip bloomed into sensation. Mind you, it is my duty here to emphasise that, at the time, nobody could have guessed that what looked like an irresponsible escapade, was to mature into a long, deep, important relationship.

But at the time all the public knew was that - as a romantic novelist might put it - Cupid's dart had hit both targets, and set the Nile on fire. And the Tiber. Even the Thames sizzled, a bit. I have an idea that the South-Wales River Tawe kept its cool.

Well, as the scandal grew and grew, I - oh, Richard, you and I have talked of this so often since, and it's so long ago it can come out now - I remembered that I had introduced you to Sybil, and that I was godfather to little Kate : I flew to Rome. Once again the heavy uncle, but this time on a mission. A romance-puncturing mission. Sitting in the plane, I did remind myself that I was playing a very bad part, was miscast, and had to pay my own fare.

I was met by our delinquent friend, and as he drove me to the studios, we talked of this and that, but not of it. then, bump - he stopped the car and looked at me. I was about to embark on my lecture, carefully prepared, when he said - I shall never forget it - he said, very calmly, 'Dwi am briodi'r eneth 'ma.' Which is Welsh for 'I am going to marry this girl.' Dwi am brioi'r eneth 'ma.

There was, in the green eyes, the twinkle - but a mischievous devilish twinkle, Miss Cooke had been right. And the fact that he'd said it in Welsh proved, to my Celtic instinct, that he was going to marry this girl. Though even a Celtic instinct could hardly foresee that he was going to do it twice.

After Rome, the dollars no longer poured. They cascaded. Up to the waist he was. Having started life as a simple child of the valleys - the smallest luxuries out of his reach - Richard Burton 'Super-Star' found himself, like an orphan with a sweet-tooth, let loose in the biggest candy-store in the world - Hollywood!

He spent lavishly. And the more he spent, the more he earned. And the Media - 'media', what a useful word, the plural of 'medium', however did we manage without it, covers everything - the Media began to mutter. As they donned the unsuitable mantles of the old Welsh-Calvinist preachers, they hinted at Mammon, and the Mess of Pottage, and the golden calf : omitting to note that while the 'Super-Star' enjoyed getting rich - who wouldn't have, who wasn't a hermit? - it was a joy he shared with a beloved family, with his friends and with countless acquaintances and causes in need of help. He was bountiful.

I remember, in Manhattan, a glimmering party, where I sat next to the elder sister who brought Richard up. He had taken Cis out shopping, and she looked stunning ; she could have been a film beauty who had retired into New York society. I complimented her on her dress. She looked round - the stars were hanging from the chandeliers, Danny Kaye, Gina Lollobrigida, Sinatra, fabulous. Cis looked round and said, 'Well, Emlyn, I thought I'd put on my Sunday-best for them all.'

No need to go into the rest of an eventful saga, with its ups and downs. Many downs, because the man had a passion for life, and where there is passion, there has to be - sooner or later - trouble. Side by side with the light, the dark ; behind exaltation....melancholy. No need to go into all that, because the Media was there, keeping the world up to date on every detail, true or false. (To be fair to them, Richard, you sure did supply them with copy! You with the cheerfully cynical attitude of the quick-witted public figure trapped in limelight - 'If they want something quotable, here goes, with salt and pepper.' And out would shout some outrageous quip, often to our detriment. But quotable).

The ups and downs....Permit me to administer a reproach. Concerning the recent obituaries and commentaries.

They're funny things, obituaries. When something like this happens, a bolt from the blue, within a couple of hours the newspapers are swarming with meticulously detailed judgements ; and we all think - 'How uncannily quick -brilliant!'

The fact is that most of the Obits, for months or even years, have been lurking in cold storage along shelves in Fleet Street, at the ready for....I was going to say 'starting gun' but what I mean, of course, is the opposite....For any of us who have done anything public, the posthumous verdicts, signed and sealed, lie in wait. Long before curtain is down. We can only hope the notices won't be too bad. and at least we have the comforting thought that we ourselves won't be tempted to rush out and buy all the papers. Richard's notices have been....mixed. Oh, much emotional affection, some of it touching, some of it toppling over into the maudlin. But when it came to the career....not much emphasis on the ups, concentration on the downs. So I'd like, quickly, to set the record a bit straighter, credits versus debits.

For instance - while there has been harping on physical indulgence, has there been any mention of the crippling illness which cut short a distinguished stage appearance in 'Camelot'? What of the days and nights of pain, endured with stubborn fortitude?

His mistakes. Of course he made mistakes - he has said so - we all make mistakes, unless at the age of ten we retire into a retreat, for life! Of course some of the films were trash, again he said so - but there have been - apart from a couple of serious articles - has there been any appreciation of such pictures as....Look Back In Anger ; The Taming Of The Shrew ; The Night Of The Iguana ; Under Milk Wood ; The Comedians ; The Spy Who Came In From The Cold ; Becket ; Anne Of The Thousand Days ; Equus ; Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, and quite recently, the immensely bold Wagner with Olivier, Gielgud and Richardson - trash?

Moreover, while the film only just completed has been mentioned by name, well it has to be - has anybody remarked that 1984, with a subject infinitely disturbing - is patently a venture worthy of respect? And is it not to reflect that all these performances are permanent? Which leaves....the accusation that he turned his back on the serious theatre, in order to worship that wicked old mammon. No salute to the three returns to the same 'serious theatre' . First, at the Playhouse Oxford, Doctor Faustus. No slouch Chris Marlowe. Or Nevill Coghill....

Then two theatre gambles, which he won. First, his appearance in that fine play Equus, on Broadway, where two stars had already been successful in the same part. Second again on Broadway, at the height of his 'Super-star' combo....Hamlet, directed by Gielgud, a run which broke John Barrymore's record.

Finally, no mention of the fact that when this sadness hit us, the man was in fine shape. Richard was himself again. Which meant there was a good chance that he might, in a year or two, fulfil a dream, of his and others : a return to the English poetry which he cherished with all his Welsh heart. As Prospero. As Lear.

After that, I don't much like going back to his 'notices',but -two brisk quotes, and I have done. Very brisk, they are one word each. at least two journalists had the cheek to tap out, on their typewriters the word 'failure'. well...if a man is a failure who, on leaving this planet, monopolizes the front page of every national newspaper throughout the Western World - then quite a few mortals would give anything to be such a failure.

And what of the other word, which has recurred so often that it has become a cliche - the word 'flawed' , f-l-a-w-e-d, - 'a flawed career' and so on. But this word happens to imply a compliment. Because it takes a precious stone to be flawed. and we have here....a precious stone.

We thank you, ein annwyl Richard, for your shining gifts, for your love of your devoted wife, of your family, of your friends, of your country, and of life. And thank you for....that twinkle in the eye. I can only think at this moment, of Upper St Martin's Lane. A boy of seventeen, standing in the black-out, spouting poetry. Imperishable. And death....shall have no dominion.

Emlyn Williams died at home in Chelsea on the 25th of September, 1987. He was eighty-one years old.

The photograph of Emlyn Williams is credited to BBC Cymru / Wales

George Emlyn Williams was born in Glan-Yr-Afon, Mostyn, Flintshire on the 26th of November, 1905.

After being schooled at Hollywell Grammar School, for which he had won a scholarship, he attended Christ Church, Oxford, where he read French and Italian and joined the Oxford University Dramatic Society, which was where he discovered his taste for the theatre and in particular his talent in the art of play-writing.

In 1927, at the age of eighteen, Emlyn Williams joined a small repertory company and by 1930 had begun writing himself, his early works included the titles, 'A Murder Has Been Arranged' and 'The Late Christopher Bean', a successful comedy-drama which opened at The St. James Theatre, London on May the 16th,1933 and which ran for a total of four hundred and thirty-three performances.

It was however his 1935 play, 'A Night Must Fall', that brought him recognition and fame. 'Night Must Fall', was a psychological thriller which was later adapted twice for film, the first, and most successful being in 1937 which starred Robert Montgomery and Rosalind Russell.

Success followed success and in 1938 he wrote 'The Corn Is Green', probably the play which Emlyn Williams will be most remembered for. This too was adapted for the big screen, being released in 1945 by Warner Brothers and starring two great character actors, Bette Davis and Nigel Bruce.

It was in 1944 however, with his next play, 'The Druid's Rest', that Emlyn Williams became involved in the life, and career, of Richard Burton.

More information on 'The Druid's Rest' and Emlyn Williams' involvement in the life and career of Richard Burton can be found on the 'Richard Burton In The Theatre' and 'Burton Books and Magazines' pages of this website.

As well as stage-plays, Emlyn William's was a prolific writer of screenplays, which included working with Alfred Hitchcock on 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' which was released in 1956 by Paramount Pictures and starred James Stewart and Doris Day.

Emlyn Williams also began to appear in various films himself including the classic films, 'They Drive By Night', 'The Citadel', 'Jamaica Inn', and of course, 'The Last Day's Of Dolwyn'.

Written and directed by, and starring Emlyn Williams himself, 'The Last Day's Of Dolwyn' is notable for being the film in which Richard Burton would make his screen debut. In a part especially written for him, Richard Burton would play the role of Gareth, a part requiring him to speak both Welsh and English, starring alongside Edith Evans, Hugh Griffith and Emlyn Williams himself.

As well as appearing in his own plays, Emlyn Williams took two 'one-man shows' on tour, the first in which he portrayed Charles Dickens and the second, Dylan Thomas in the production entitled, 'A Boy Growing Up'.

Emlyn Williams was also the author of two autobiographies and the best selling 'True-Crime' work, 'Beyond Belief - A Chronicle of Murder and Detection', which was an in-depth study of the infamous 'Moors Murders' of the late sixties.

From 1935 Emlyn Williams was married to the actress Mary O' Shann with whom they had two sons, Alan, who became a writer, and Brook, who became close to Richard Burton and was employed by him as a personal assistant and who can often be seen in many of Richard Burton's films in small cameo roles.

Emlyn Williams was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1962.

A lifelong friend of Richard Burton, he was instrumental in the introduction of Burton to his first wife Sybil, was Godfather to Burton's daughter Kate, and read a moving eulogy at Richard Burton's Memorial Service, held in London, in August, 1984. A deeply personal and moving piece of writing, it reads in it's entirety;

Our dear Richard...Or, the way I used to start a letter to you - Annwyl Richard...Our dear Richard, here we all are, joining Sally and Kate and all your family in thinking about you, and talking about you. Yes, I can see the old twinkle in the eye, as if to say - 'Well, now that the smoke's clearing away...what are you going to say about me? Not going to be easy, is it?' How often, in the past few weeks, have my thoughts gone back to the first time you and I met, forty-one years ago next month! We spoke of that first meeting, you remember, at our last meeting, in New York a year ago...

It was one evening in Cardiff, in 1943, the Sandringham Hotel, where I was interviewing possible Welsh-speaking actors for a new play. After a dismal procession of no-goods, an older man introduced himself as the schoolmaster who had written about a pupil, apparently a promising amateur. He beckoned, and the pupil stepped forward : a boy of seventeen, of startling beauty, and quiet intelligence. He looked - as very special human beings tend to look at that age - he looked imperishable.

I asked young Jenkins what was the last part he had played, at school. The answer came clear as a bell, 'Professor Higgins in Pygmalion.' I was later to realise the added incongruity of that : the schoolmaster - the unique Phil Burton - was, at that time, playing a real-life Higgins to a markedly male Eliza.

At rehearsals in London, it was interesting to watch the boy work, for he did something very rare : he drew attention by not claiming it. He played his part with the perfect simplicity needed, and offstage was quietly pleasant - not shy, just...reserved - except for the sudden smile, which - there is no other word for it - glowed. He didn't talk much. I think he was a bit self-conscious about his accent, and the need to work on it - it's a phase actors sometimes go through. But inside there, there was humour. A twinkle in the eye, no doubt about it. One evening, as he and I walked away from a late rehearsal, I asked what was the book he was carrying. 'Dylan Thomas'. I just knew the name. 'He is a great poet.' Then he suddenly stopped, and recited. The words resounded through the blackout of the deserted street : Upper St.Martin's Lane, just up the road. 'They shall have stars at elbow and foot...'

I did not say to myself, in a flash, 'This lad will be famous!' But it did occur to me that here was more than a well-graced adolescent who could speak lines naturally, this was a 'voice'. And behind the 'voice' a mind which, like my own, was in love with the English language.

Then I asked him, in an avuncular manner - I was thirty-seven - if his digs were all right, and was he behaving himself in London? he said he was. Even then I doubted it.

Oh, the English language - let me touch, in passing, on something which - up till now - has only been known by those closest to him. His devotion to spoken English has over the last years, extended to words on paper. Steadily, unobtrusively, he has been writing. Diaries? Autobiography? Time will tell, and may surprise. Anyway...

Back to spoken English. After the war, five years of invaluable stage experience, with in between, several films. Then in the early fifties, the young actor's life was taken over by Shakespeare, at 'Stratford' and the 'Old Vic'. They were salaries you couldn't save on, but gruelling hard work built up to triumph.

My former school-teacher, Miss Cooke, was curious about this second Welsh peasant who had been seduced into the theatre and I presented him to her. Richard was on his best behaviour. But she did say afterwards, 'He's going to do well, what's more he's got the devil in him. You haven't.' I felt commonplace.

Then - America! The Movies, Capital 'M', and - and even bigger capital 'M' - the money! The dollars poured in.

Then - 1962. Which means we have to touch lightly - no names mentioned - on a certain Roman - Egyptian epic. (I nearly said 'a Roman - Elizabethan epic')...Gossip bloomed into sensation. Mind you, it is my duty here to emphasise that, at the time, nobody could have guessed that what looked like an irresponsible escapade, was to mature into a long, deep, important relationship.

But at the time all the public knew was that - as a romantic novelist might put it - Cupid's dart had hit both targets, and set the Nile on fire. And the Tiber. Even the Thames sizzled, a bit. I have an idea that the South-Wales River Tawe kept its cool.

Well, as the scandal grew and grew, I - oh, Richard, you and I have talked of this so often since, and it's so long ago it can come out now - I remembered that I had introduced you to Sybil, and that I was godfather to little Kate : I flew to Rome. Once again the heavy uncle, but this time on a mission. A romance-puncturing mission. Sitting in the plane, I did remind myself that I was playing a very bad part, was miscast, and had to pay my own fare.

I was met by our delinquent friend, and as he drove me to the studios, we talked of this and that, but not of it. then, bump - he stopped the car and looked at me. I was about to embark on my lecture, carefully prepared, when he said - I shall never forget it - he said, very calmly, 'Dwi am briodi'r eneth 'ma.' Which is Welsh for 'I am going to marry this girl.' Dwi am brioi'r eneth 'ma.

There was, in the green eyes, the twinkle - but a mischievous devilish twinkle, Miss Cooke had been right. And the fact that he'd said it in Welsh proved, to my Celtic instinct, that he was going to marry this girl. Though even a Celtic instinct could hardly foresee that he was going to do it twice.

After Rome, the dollars no longer poured. They cascaded. Up to the waist he was. Having started life as a simple child of the valleys - the smallest luxuries out of his reach - Richard Burton 'Super-Star' found himself, like an orphan with a sweet-tooth, let loose in the biggest candy-store in the world - Hollywood!

He spent lavishly. And the more he spent, the more he earned. And the Media - 'media', what a useful word, the plural of 'medium', however did we manage without it, covers everything - the Media began to mutter. As they donned the unsuitable mantles of the old Welsh-Calvinist preachers, they hinted at Mammon, and the Mess of Pottage, and the golden calf : omitting to note that while the 'Super-Star' enjoyed getting rich - who wouldn't have, who wasn't a hermit? - it was a joy he shared with a beloved family, with his friends and with countless acquaintances and causes in need of help. He was bountiful.

I remember, in Manhattan, a glimmering party, where I sat next to the elder sister who brought Richard up. He had taken Cis out shopping, and she looked stunning ; she could have been a film beauty who had retired into New York society. I complimented her on her dress. She looked round - the stars were hanging from the chandeliers, Danny Kaye, Gina Lollobrigida, Sinatra, fabulous. Cis looked round and said, 'Well, Emlyn, I thought I'd put on my Sunday-best for them all.'

No need to go into the rest of an eventful saga, with its ups and downs. Many downs, because the man had a passion for life, and where there is passion, there has to be - sooner or later - trouble. Side by side with the light, the dark ; behind exaltation....melancholy. No need to go into all that, because the Media was there, keeping the world up to date on every detail, true or false. (To be fair to them, Richard, you sure did supply them with copy! You with the cheerfully cynical attitude of the quick-witted public figure trapped in limelight - 'If they want something quotable, here goes, with salt and pepper.' And out would shout some outrageous quip, often to our detriment. But quotable).

The ups and downs....Permit me to administer a reproach. Concerning the recent obituaries and commentaries.

They're funny things, obituaries. When something like this happens, a bolt from the blue, within a couple of hours the newspapers are swarming with meticulously detailed judgements ; and we all think - 'How uncannily quick -brilliant!'

The fact is that most of the Obits, for months or even years, have been lurking in cold storage along shelves in Fleet Street, at the ready for....I was going to say 'starting gun' but what I mean, of course, is the opposite....For any of us who have done anything public, the posthumous verdicts, signed and sealed, lie in wait. Long before curtain is down. We can only hope the notices won't be too bad. and at least we have the comforting thought that we ourselves won't be tempted to rush out and buy all the papers. Richard's notices have been....mixed. Oh, much emotional affection, some of it touching, some of it toppling over into the maudlin. But when it came to the career....not much emphasis on the ups, concentration on the downs. So I'd like, quickly, to set the record a bit straighter, credits versus debits.

For instance - while there has been harping on physical indulgence, has there been any mention of the crippling illness which cut short a distinguished stage appearance in 'Camelot'? What of the days and nights of pain, endured with stubborn fortitude?

His mistakes. Of course he made mistakes - he has said so - we all make mistakes, unless at the age of ten we retire into a retreat, for life! Of course some of the films were trash, again he said so - but there have been - apart from a couple of serious articles - has there been any appreciation of such pictures as....Look Back In Anger ; The Taming Of The Shrew ; The Night Of The Iguana ; Under Milk Wood ; The Comedians ; The Spy Who Came In From The Cold ; Becket ; Anne Of The Thousand Days ; Equus ; Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, and quite recently, the immensely bold Wagner with Olivier, Gielgud and Richardson - trash?

Moreover, while the film only just completed has been mentioned by name, well it has to be - has anybody remarked that 1984, with a subject infinitely disturbing - is patently a venture worthy of respect? And is it not to reflect that all these performances are permanent? Which leaves....the accusation that he turned his back on the serious theatre, in order to worship that wicked old mammon. No salute to the three returns to the same 'serious theatre' . First, at the Playhouse Oxford, Doctor Faustus. No slouch Chris Marlowe. Or Nevill Coghill....

Then two theatre gambles, which he won. First, his appearance in that fine play Equus, on Broadway, where two stars had already been successful in the same part. Second again on Broadway, at the height of his 'Super-star' combo....Hamlet, directed by Gielgud, a run which broke John Barrymore's record.

Finally, no mention of the fact that when this sadness hit us, the man was in fine shape. Richard was himself again. Which meant there was a good chance that he might, in a year or two, fulfil a dream, of his and others : a return to the English poetry which he cherished with all his Welsh heart. As Prospero. As Lear.

After that, I don't much like going back to his 'notices',but -two brisk quotes, and I have done. Very brisk, they are one word each. at least two journalists had the cheek to tap out, on their typewriters the word 'failure'. well...if a man is a failure who, on leaving this planet, monopolizes the front page of every national newspaper throughout the Western World - then quite a few mortals would give anything to be such a failure.

And what of the other word, which has recurred so often that it has become a cliche - the word 'flawed' , f-l-a-w-e-d, - 'a flawed career' and so on. But this word happens to imply a compliment. Because it takes a precious stone to be flawed. and we have here....a precious stone.

We thank you, ein annwyl Richard, for your shining gifts, for your love of your devoted wife, of your family, of your friends, of your country, and of life. And thank you for....that twinkle in the eye. I can only think at this moment, of Upper St Martin's Lane. A boy of seventeen, standing in the black-out, spouting poetry. Imperishable. And death....shall have no dominion.

Emlyn Williams died at home in Chelsea on the 25th of September, 1987. He was eighty-one years old.

The photograph of Emlyn Williams is credited to BBC Cymru / Wales

The Blue Plaque located at 60 Marchmont Street, London, commemorating the time Emlyn Williams lived at the address.

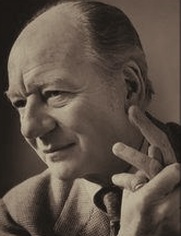

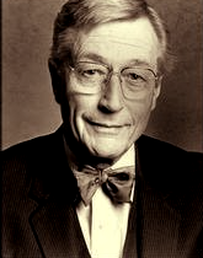

Sir John Gielgud

Arthur John Gielgud was born in South Kensington on the 14th of April, 1904. The youngest of three sons born to Frank and Kate Terry-Gielgud, he was destined to become in some way connected to the theatre as his mother, an actress till she married, was a member of the famous theatrical dynasty which included Ellen, Fred and Marion Terry.

It was whilst being educated at the Hillside Preparatory School in Surrey that the young John Gielgud first discovered his love of theatre, which the school actively encouraged, casting him in various amateur Shakesperian roles such as Mark Anthony in 'Julius Caesar' and Shylock in 'The Merchant Of Venice'.

Following Hillside, he was then educated at the Westminster School where as he was to later recall he had easy access to the West End... "Just in time to touch the fringe of the great century of the theatre'. Upon leaving the Westminster School in 1921 he persuaded his parents to allow him to attend acting lessons under the tutelage of Constance Benson, the wife of actor and manager, Sir Frank Benson. His theatrical debut came in November 1921 playing an uncredited Herald in 'Henry V' at the Old Vic. A colleague at the time recognised his talent and recommended he apply to The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and in 1923 Gielgud won a scholarship there and was trained by, among others, the actor Claude Rains.

His major breakthrough came with the assistance of his famous family. In 1922 his famous cousin Phillis Nelson-Terry invited him on tour as an understudy, assistant stage-manager and walk-on actor. It was a highly successful tour with the outcome being that John Gielgud would be invited to join the Oxford Players Repertory Theatre.

Gielgud's theatre career flourished during the 1920's,with Gielgud appearing in a variety of roles, and in 1924 he made his screen debut in Walter Summers' silent film, 'Who Is the Man', however, John Gielgud's big break was to be not on screen but on the stage at The Old Vic.

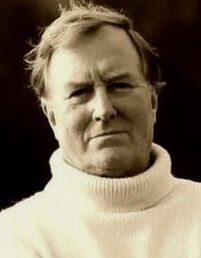

The photograph of Sir John Gielgud ¨which appears here is credited to Godfrey Argent and is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Arthur John Gielgud was born in South Kensington on the 14th of April, 1904. The youngest of three sons born to Frank and Kate Terry-Gielgud, he was destined to become in some way connected to the theatre as his mother, an actress till she married, was a member of the famous theatrical dynasty which included Ellen, Fred and Marion Terry.

It was whilst being educated at the Hillside Preparatory School in Surrey that the young John Gielgud first discovered his love of theatre, which the school actively encouraged, casting him in various amateur Shakesperian roles such as Mark Anthony in 'Julius Caesar' and Shylock in 'The Merchant Of Venice'.

Following Hillside, he was then educated at the Westminster School where as he was to later recall he had easy access to the West End... "Just in time to touch the fringe of the great century of the theatre'. Upon leaving the Westminster School in 1921 he persuaded his parents to allow him to attend acting lessons under the tutelage of Constance Benson, the wife of actor and manager, Sir Frank Benson. His theatrical debut came in November 1921 playing an uncredited Herald in 'Henry V' at the Old Vic. A colleague at the time recognised his talent and recommended he apply to The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and in 1923 Gielgud won a scholarship there and was trained by, among others, the actor Claude Rains.

His major breakthrough came with the assistance of his famous family. In 1922 his famous cousin Phillis Nelson-Terry invited him on tour as an understudy, assistant stage-manager and walk-on actor. It was a highly successful tour with the outcome being that John Gielgud would be invited to join the Oxford Players Repertory Theatre.

Gielgud's theatre career flourished during the 1920's,with Gielgud appearing in a variety of roles, and in 1924 he made his screen debut in Walter Summers' silent film, 'Who Is the Man', however, John Gielgud's big break was to be not on screen but on the stage at The Old Vic.

The photograph of Sir John Gielgud ¨which appears here is credited to Godfrey Argent and is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Christopher Fry

Born Arthur Hammond Harris in Bristol on the 18th of December, 1907, the son of a Master Builder and Lay Preacher. At an early age he took on his mother's maiden name in the mistaken belief that she was related to the 19th Century prison reformer and Quaker, Elizabeth Fry.

It was whilst still at school in Bedford that he developed a skill and life-long love of writing, mostly amateur plays, and upon leaving school he took up the career of schoolteacher at the prestigious Hazelwood school in Surrey.

Fry gave up teaching in 1932 to pursue a career in the theatre, founding the Tunbridge Wells Repertory Players, which ran for three years, during which time he directed and starred in the English theatrical premiere of George Bernard Shaw's play, 'A Village Wooing'.

His recognition as a playwright and dramatist of some renown came about after he was commissioned by the Vicar of Steyning, West Sussex to write a play celebrating the life of a local Saint, Cuthman of Steyning. This work was to become, 'The Boy With A Cart', which opened at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith in the January of 1950 with Richard Burton in the title role of Cuthman.

In 1939 he was appointed Artistic Director of the Oxford Playhouse, however this position was cut short due to the outbreak of war on September the 3rd, 1939. Fry had grown up as a pacifist and during the war he was a conscientious objector. He served in the Non-Combatant Corps, during which time his duties were to clean the vast underground complex of London's sewers.

Just after the war, Christopher Fry wrote the comedy play, 'A Phoenix Too Frequent', based on the play originally written by Petronius. The play opened at the Mercury Theatre, Notting Hill Gate in 1946 with Paul Scofield in the role of Tegeus, the part being taken over in 1950 by Richard Burton in the production which opened at the Dolphin Theatre, Brighton.

Two other plays followed in quick succession, 'The Firstborn' and 'Thor, With Angels', the latter being commissioned by the Canterbury Festival.

Christopher Fry's most famous work however has to be his poetic, historical drama, 'The Lady's Not For Burning'. This was to be the play which would bring Richard Burton's name to the attention of the British and American theatre-going public and cement his name as one of the most important theatrical actors of his generation.

The play was commissioned by Alec Clunes, manager of the Arts Theatre in London. After a provincial run the play opened at the Globe Theatre in London and enjoyed a nine-month run. Starring alongside Richard Burton were John Gielgud and Claire Bloom. The play transferred to Broadway in 1950, to a very responsive American audience and the play can certainly be credited for a revival in popularity for poetic drama, especially of a historical kind.

Sadly, with the advent of the 'Angry Young Man' genre of British cinema in the 1950's, of which Richard Burton played a part with his role of Jimmy Porter in the magnificent film 'Look Back In Anger', Christopher Fry's style of poetic drama fell out of fashion with the general public. He did however continue to write plays, 'Curtmantle', commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company, is one fine example.

Christopher Fry lived out his last years in the village of East Dean in West Sussex. He died, in Chichester, on the 30th of June, 2005. He was ninety-seven years old.

The photograph of Christopher Fry which appears here is credited to Godfrey Argent, captured in 1970, and is on display in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born Arthur Hammond Harris in Bristol on the 18th of December, 1907, the son of a Master Builder and Lay Preacher. At an early age he took on his mother's maiden name in the mistaken belief that she was related to the 19th Century prison reformer and Quaker, Elizabeth Fry.

It was whilst still at school in Bedford that he developed a skill and life-long love of writing, mostly amateur plays, and upon leaving school he took up the career of schoolteacher at the prestigious Hazelwood school in Surrey.

Fry gave up teaching in 1932 to pursue a career in the theatre, founding the Tunbridge Wells Repertory Players, which ran for three years, during which time he directed and starred in the English theatrical premiere of George Bernard Shaw's play, 'A Village Wooing'.

His recognition as a playwright and dramatist of some renown came about after he was commissioned by the Vicar of Steyning, West Sussex to write a play celebrating the life of a local Saint, Cuthman of Steyning. This work was to become, 'The Boy With A Cart', which opened at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith in the January of 1950 with Richard Burton in the title role of Cuthman.

In 1939 he was appointed Artistic Director of the Oxford Playhouse, however this position was cut short due to the outbreak of war on September the 3rd, 1939. Fry had grown up as a pacifist and during the war he was a conscientious objector. He served in the Non-Combatant Corps, during which time his duties were to clean the vast underground complex of London's sewers.

Just after the war, Christopher Fry wrote the comedy play, 'A Phoenix Too Frequent', based on the play originally written by Petronius. The play opened at the Mercury Theatre, Notting Hill Gate in 1946 with Paul Scofield in the role of Tegeus, the part being taken over in 1950 by Richard Burton in the production which opened at the Dolphin Theatre, Brighton.

Two other plays followed in quick succession, 'The Firstborn' and 'Thor, With Angels', the latter being commissioned by the Canterbury Festival.

Christopher Fry's most famous work however has to be his poetic, historical drama, 'The Lady's Not For Burning'. This was to be the play which would bring Richard Burton's name to the attention of the British and American theatre-going public and cement his name as one of the most important theatrical actors of his generation.

The play was commissioned by Alec Clunes, manager of the Arts Theatre in London. After a provincial run the play opened at the Globe Theatre in London and enjoyed a nine-month run. Starring alongside Richard Burton were John Gielgud and Claire Bloom. The play transferred to Broadway in 1950, to a very responsive American audience and the play can certainly be credited for a revival in popularity for poetic drama, especially of a historical kind.

Sadly, with the advent of the 'Angry Young Man' genre of British cinema in the 1950's, of which Richard Burton played a part with his role of Jimmy Porter in the magnificent film 'Look Back In Anger', Christopher Fry's style of poetic drama fell out of fashion with the general public. He did however continue to write plays, 'Curtmantle', commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company, is one fine example.

Christopher Fry lived out his last years in the village of East Dean in West Sussex. He died, in Chichester, on the 30th of June, 2005. He was ninety-seven years old.

The photograph of Christopher Fry which appears here is credited to Godfrey Argent, captured in 1970, and is on display in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

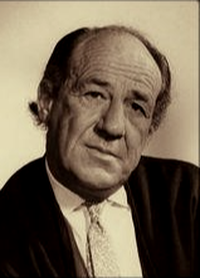

Sir Anthony Quayle

John Anthony Quayle was born on the 7th of September, 1913 in Southport, Lancashire, and was educated at both the Adderley Hall and Rugby Schools before moving on to Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London.

After a brief career in music hall, he discovered his true calling was for classical theatre and so joined The Old Vic Company in 1932.

His acting career was interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1939 and Quayle served firstly as an officer before joining the Special Operations Executive, an experience that affected him deeply and a time he never talked about thereafter.

In 1948 he was back in theatre, and became the director at The Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, the forerunner of The Royal Shakespeare Company, and it was around this time he first came into contact with Richard Burton.

Quayle had witnessed Burton's incredible performance in Christopher Fry's, 'The Boy With A Cart' at The Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith and had invited him to join the cast in the 1951 Cycle Of Historical Plays at Stratford. Burton's introduction to Shakespeare saw him take the roles in Henry IV ( Parts I and II ), The Tempest, and Henry V. Anthony Quayle's roles during this season saw him take on Falstaff, Othello and parts in Henry VIII, Titus Andronicus and Much Ado About Nothing.

It was from 1956 that Anthony Quayle's film career began to take off. Some of the films in which he was to appear include such classics as, 'Ice Cold In Alex', 'The Guns Of Navarone', 'Lawrence Of Arabia', 'A Study In Terror', and 'The Eagle Has Landed'.

He was to appear on film with Richard Burton just once, in the 1969 historical drama, 'Anne Of The Thousand Days', cast as Cardinal Wolsey alongside Burton as Henry VIII.

Anthony Quayle returned to the theatre in 1970 and achieved critical acclaim for his role in 'Sleuth', written by Anthony Shaffer, (who wrote the screenplay for the 1978 Richard Burton film, 'Absolution'), and was presented with the Drama Desk Award for that year.

In 1984 Quayle formed the Compass Theatre Company, touring in plays such as, 'Saint Joan' and 'King Lear', with Quayle in the title role.

Anthony Quayle was knighted for his services to theatre in 1985.

He died, aged 76, at home in Chelsea, on the 20th of October, 1989.

The above photograph of Sir Anthony Quayle is credited to Godfrey Argent and is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

John Anthony Quayle was born on the 7th of September, 1913 in Southport, Lancashire, and was educated at both the Adderley Hall and Rugby Schools before moving on to Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London.

After a brief career in music hall, he discovered his true calling was for classical theatre and so joined The Old Vic Company in 1932.

His acting career was interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1939 and Quayle served firstly as an officer before joining the Special Operations Executive, an experience that affected him deeply and a time he never talked about thereafter.

In 1948 he was back in theatre, and became the director at The Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, the forerunner of The Royal Shakespeare Company, and it was around this time he first came into contact with Richard Burton.

Quayle had witnessed Burton's incredible performance in Christopher Fry's, 'The Boy With A Cart' at The Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith and had invited him to join the cast in the 1951 Cycle Of Historical Plays at Stratford. Burton's introduction to Shakespeare saw him take the roles in Henry IV ( Parts I and II ), The Tempest, and Henry V. Anthony Quayle's roles during this season saw him take on Falstaff, Othello and parts in Henry VIII, Titus Andronicus and Much Ado About Nothing.

It was from 1956 that Anthony Quayle's film career began to take off. Some of the films in which he was to appear include such classics as, 'Ice Cold In Alex', 'The Guns Of Navarone', 'Lawrence Of Arabia', 'A Study In Terror', and 'The Eagle Has Landed'.

He was to appear on film with Richard Burton just once, in the 1969 historical drama, 'Anne Of The Thousand Days', cast as Cardinal Wolsey alongside Burton as Henry VIII.

Anthony Quayle returned to the theatre in 1970 and achieved critical acclaim for his role in 'Sleuth', written by Anthony Shaffer, (who wrote the screenplay for the 1978 Richard Burton film, 'Absolution'), and was presented with the Drama Desk Award for that year.

In 1984 Quayle formed the Compass Theatre Company, touring in plays such as, 'Saint Joan' and 'King Lear', with Quayle in the title role.

Anthony Quayle was knighted for his services to theatre in 1985.

He died, aged 76, at home in Chelsea, on the 20th of October, 1989.

The above photograph of Sir Anthony Quayle is credited to Godfrey Argent and is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

John Neville

John Reginald Neville was born in Willesden, London on the 2nd of July, 1925 to working-class parents Mabel and Reginald Neville, a lorry driver. He was educated at the Willesden and Chiswick School for Boys and after National Service, in which he served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, he continued his education, training as an actor at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, after which he joined the theatrical company, The Trent Players.

Hailed as one of the most potent stage actors of the 1950's, his talent and 'Matinee Idol' good looks soon saw him rise up to become one of the leading players of London's 'Old Vic' company. It was during this time that he was first cast alongside the rising talent of Richard Burton.

Richard Burton had already proved himself to be the 'star' of the English Shakespearean stage with his performances at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford in 1951 in the roles of Henry IV and Ferdinand in The Tempest, and now John Neville found himself cast alongside Richard Burton at The Old Vic in the 1953/4 productions of Hamlet, King John, Coriolanus and Twelfth Night as well as the 1955 production of Henry V. It was during this time that Richard Burton and John Neville became firm friends.

It was, however, their combined performance in the Shakespeare play, 'Othello' for which they became best known and it is a performance for which some actors and directors still talk about to this day.

Between themselves they decided to take on the mammoth task of alternating nightly the roles of Othello and Iago, a feat which had never been considered before, let alone been undertaken. The Old Vic 1955 production of 'Othello' made headlines, and the two actors became superstars of the English stage overnight.

Burton, in his early theatre career had always been looked upon as the natural successor to Olivier and John Neville, with his good looks, distinctive voice and in-born modesty was naturally considered to be the one actor who could slip easily into Sir John Gielgud's comfortable shoes.

Sadly Richard Burton and John Neville never appeared on screen together.

Following his success at The Old Vic and at The Bristol Old Vic, John Neville joined the Nottingham Playhouse becoming joint artistic director alongside Frank Dunlop and Peter Ustinov. The trio soon built up the reputation of the theatre making it one of the country's leading provincial repertory theatres. John Neville held this position until 1967.

In 1969 John Neville took on his first major television role, starring in the B.B.C.2 series. 'The First Churchills'. The programme was also broadcast in the United States, gaining him immediate international recognition.